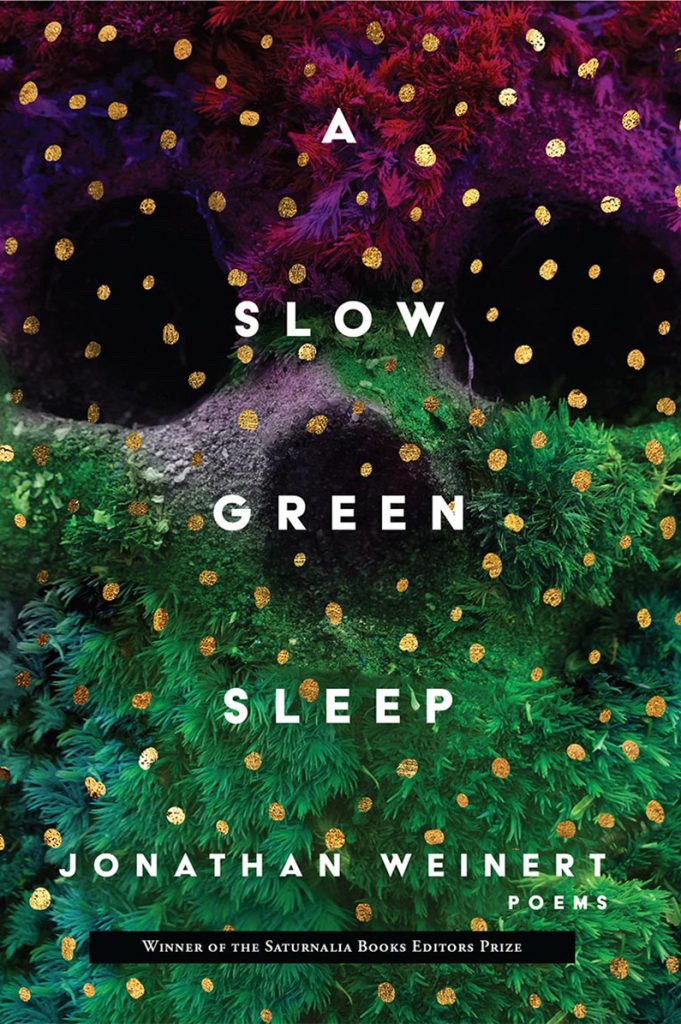

Winner of the Saturnalia Books Editors Prize

A Slow Green Sleep takes the long view: from the prehistoric through the human historic and on to the posthistoric. Voices speak out of fresh and ancient graves, from the recent and distant pasts, and from some possible and probable futures. Will the human experiment fail, or change? Can we stop loving “the wrongest things,” finding beauty instead in self-effacement and the certainty that the earth will live on without us? Can we come to consider other people, and our nonhuman others, as equal in importance to ourselves? The poems in A Slow Green Sleep use various formal strategies to make resting places where one can embrace how the world is with us today, and how it will be hereafter.

Opening with the startling words “When we were dead,” this gorgeous book moves seamlessly through time, from a post-apocalyptic world that is eerily like our own back to a history that precedes our human intrusions. The threat of extinction hovers over the book, as the poet—a “connoisseur of disappearances”—catalogs “memories of things / that have almost finished vanishing.” In the midst of shadow and darkness, Weinert’s lush language and lyric intensity green a world that may be heading toward sleep, but that comes alive and shining even as “the white pines wait for us / to not be here again.”

— Martha Collins, author of Because What Else Could I Do and Night Unto Night

Jonathan Weinert’s A Slow Green Sleep is an astonishing and visionary book of poetic eco-witnessing that combines W. S. Merwin’s stoic political engagement with Wallace Stevens’ self-awareness of the mind at work. But even as the poems consider the terror of apocalypse, Weinert’s touch is so gentle—so anti-ego—that the effect is one of poignant acquiescence as Weinert repeatedly places the invisible dot of the self inside the vast trajectory of ecological time. Here where “the bluescreened faces / of the fiercest predators the earth has ever seen / pretend to a devastating mildness”—where we can’t help but pledge allegiance “to the flag of the united states of the visible”—there’s a certain comfort in the fact that “estrangement is only human,” and there persists the hope that “[w]e are going to live on / despite / incursions in the genome.” This book is profoundly of our moment—not to mention wise and deft and moving.

— Wayne Miller, author of Post- and The City, Our City

I wept reading the poems in A Slow Green Sleep, where cities and neighborhoods have already fallen, and where, after we “sent our certainty over all the earth,” all that remains for the future is our “cellphone chipsets, / diapers, filings, clickers, toilet seats, / the petrified remains of hot-drink cups.” What is truly extraordinary and puzzling with each read of this important collection is how exactly Jonathan Weinert manages to write poems that sing right into the heartbreaking crisis of our earth’s destruction and are at the same time so unbelievably beautiful. I believe the answer is abiding love, love which permeates every word, every line, every page. A Slow Green Sleep is a tremendous achievement.

— Victoria Redel, author of Before Everything and Woman Without Umbrella

“Necropastorals” is the title of a poem in Jonathan Weinert’s haunted, earthy, outstanding new poetry collection, A Slow Green Sleep, and the word speaks to the death-nature nexus that Weinert excavates so deftly. There’s an attentive, mournful mood, a sense of trying to make oneself at home with rot-present and rot-future. Weinert laments: “We humans love the wrongest things: eternity,/ our histories, our brains.” And he pairs the fumes, motor roars, smartphones with the oaks, the crows, the rain. There’s a frothy, fervent feel to the book, an alchemical energy that seethes. His lines spill and split like seeds in “a kingdom for milkweed and lichen and spider and mold.” Read it out loud: “Here’s a recipe for seeing: slow green sleep,/ and feeling as a long-expected season feels/ the day the sky entrusts its new campaign/ of sails and sheets.” People stare “with their flatscreen eyes,” and Weinert looks to what is “wet and animal.” There is something fearful here, and potent, and ferociously, elementally, true.

— Nina MacLaughlin, The Boston Globe